Jonathan Cobb, senior programme leader, climate, at World Nuclear Association, was in Baku, Azerbaijan, and he tells the World Nuclear News podcast that although there was no direct reference to nuclear energy in the agreement eventually reached at COP29, there was further progress among the "coalition of the willing" with six more countries signing up to the New Zero Nuclear goal of tripling nuclear capacity by 2050.

You can listen to the full interview on all good podcast platforms or via the embedded player on this page. An edited digest of the interview with Cobb is below

What is a COP?

COP stands for Conference of the Parties, where the parties are the governments who signed up to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, which sought to stabilise concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at levels which didn't harm the environment. The Kyoto Protocol set the first targets for developed countries - there were 24 of these, although the number of countries was higher because the European Union counted as one party. Efforts at COPs to set specific emission reduction targets for individual countries were unsuccessful and the approach has changed to efforts to limit global temperature increases to less than 2 degrees Celsius - ideally less than 1.5°C - above pre-industrial levels. This year we may well see a global temperature rise above 1.5°C, reflecting an urgent need to cut greenhouse gas emissions. After all these COPs, the world is yet to get to the stage of stopping rises in greenhouse gas emissions. The challenge now is that to get anywhere near hitting those temperature targets the world needs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

Developed vs developing countries

This is one of the tensions in the process because the onus has been on those countries and regions that were specified as being developed in 1992 and reflected the historic emissions there had been to that point. Now we're 32 years later and the world has changed. Economies such as China and India have expanded very rapidly over that period, and so have their greenhouse gas emissions, and yet within the COP process they remain classified as developing, with the definition and responsibilities enshrined within the United Nations Framework Convention all those years ago. It has been particularly key to conversations about providing finance from developed countries to developing countries to allow the developing countries to be able to deal with both the impacts of climate change - adapting to the impacts of climate change - but also taking measures to try to avoid their own emissions.

What was the outcome of COP29?

There was agreement eventually reached, at least in terms of voting through a text on new collective quantified goals and climate finance. It had previously been agreed that USD100 billion annually should be provided by developed countries to help developing countries with adaption and mitigation measures. Coming into COP29 there was an assessment that that figure needed to increase to USD1.3 trillion per year by 2035, but the eventual agreement was for a figure of USD300 billion while agreeing to work towards the goal of mobilising USD1.3 trillion - which can come from both state and private sectors. It also refers to some developing countries voluntarily contributing, which has been taken as a reference to China and India. It means that countries left COP29 equally unhappy, but there was also recognition that with the forthcoming return of President Donald Trump in the USA it was a case of going for the deal they could get rather than the deal they would be happy with.

How binding is the agreement?

It is certainly something that all the parties have signed up to, but there is no formal compulsion mechanism. There is a public willingness to hit this figure, but as with the USD100 billion-a-year figure, which was reached a couple of years late, there is not a specific trajectory to get to the USD300 billion figure or to the USD1.3 billion.

What about nuclear energy in COP29 agreement?

The first explicit acknowledgement within official COP texts of nuclear energy's role in being able to achieve the climate targets did not come until last year's COP28 Global Stocktake document, where it was included among the different mitigation technologies identified that parties could use to meet emission reduction targets. In early drafts this year there was a document which would have reflected back to the Global Stocktake last year with references to the paragraphs which include nuclear, but during the negotiations that text was pushed back to COP30. So there was no text within COP29 which referred to nuclear specifically, or referred back to the Global Stocktake from COP28. However there were plenty of positives for nuclear on the sidelines of COP where, increasingly, the really progressive action is taking place.

What was the good news for nuclear energy?

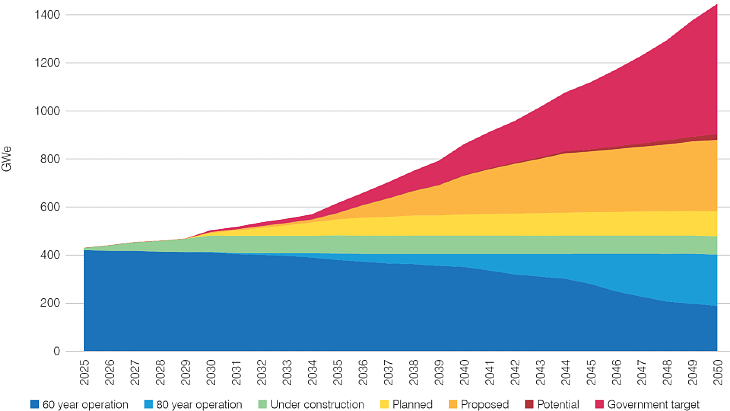

There was further progress from the so-called coalition of the willing, with further agreements on the sidelines of COP29 which saw six more countries - El Salvador, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kosovo, Nigeria and Turkey - signing up to the Net Zero Nuclear goal to triple nuclear energy capacity. (Audio from the launch event, featuring World Nuclear Association Director General Sama Bilbao y Leon, Ali Zaidi, the US White House’s national climate advisor and Abdullah Bugrahan Caravel, President of the Energy, Nuclear and Mining Research Council of Turkey, can be heard from 17 minutes 40 seconds in). There were also a number of announcements from individual countries or partnerships between countries, such as the US and Ukraine on small modular reactors, and between the UK and Finland, as well as the USA setting out a proposed roadmap to hit their 200 GW of nuclear capacity goal. (You can hear from Kirsten Cutler, Senior Strategist for Nuclear Innovation at the US Department of State, talking about the tripling target, from 23 minutes in). The Net Zero Nuclear pavilion was very busy with a full programme of events and a lot of country delegations proved to be interested in discussing their policies and options - it was a real benefit of having the country pavilions and non-governmental organisations in the same area.

Why is COP30 being seen as a more significant COP?

This is because countries have to submit their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) between COP29 and COP30, where these will be assessed. These documents will set out what countries are proposing to do. And it will then be possible to add them all together and see whether or not too little is being done to achieve the collective goal. The COP30 in Brazil in November 2025 is expected to be where there is a judgement on what countries are saying they are going to do, and an assessment of whether or not their plans are ambitious enough. There will also be some political uncertainty, with the return of President Trump to the White House, but if the USA does step back, the question will be whether it weakens the process or whether it galvanises others to step in and take that space. But with the NDCs due to be submitted for discussion at COP30, and with 31 countries now supporting the goal of tripling nuclear energy capacity, it is expected that nuclear energy will feature in a large number of the various countries' plans.

Listen and subscribe on all major podcast platforms:

World Nuclear News podcast homepage

Apple

Spotify

Amazon Music

Episode credit: Presenter Alex Hunt. Co-produced and mixed by Pixelkisser Production.

_19544_40999.jpg)

_66668.jpg)